Recently I touched base with my friend Kathy to talk about the current state of the women’s movement. Kathy noticed things that needed tojust get done that weren’t being addressed. She asked: Why were people still debating some of the same feminist issues her generation had taken on decades earlier? Let’s get moving, she exclaimed impatiently!

I responded from my broad-view perspective as a historian: I agree with you, Kathy. But isn’t it sobering to see the need to keep multi-generational dialogue alive because often decades of optimism and progress are hinged into surprising set backs and retrenchments and the door is closed? Until the next spring time of collective energy pushes forward, again.

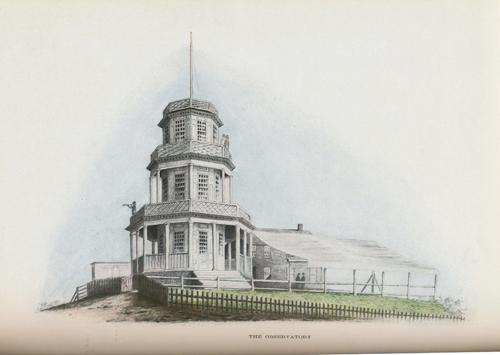

Let’s stop referring to the woman who founded RISD as “the wife of a wealthy industrialist, Jesse Metcalf”. The orphaned 14-year old Helen Adelia Rowe moved to Providence, RI in 1844 with her brothers and helped her siblings publish their own newspaper and run their own newspaper shop + tea house at the base of College Hill. Sadly, the amazing plans the Rowe had to transform this Observatory at India Point into a destination at the head of Narragansett Bay did not work out. Helen Rowe’s second brother died in 1852, and only a few days later she married Jesse Metcalf, while her one surviving brother immigrated to Australia. What did Helen Rowe do on her wedding day? Sign a contract using her maiden name, to redeem a loan she had made to the family newspaper business. She was 22.

Recently I’ve been learning about the history of women’s property rights and the distinctively Anglo-American legal system our country is founded upon. Here is a topic where progress can be noted by the century, if not longer.

For example, in the 20th century women were finally recognized as citizens who could vote (in a country founded in 1776). And in the 19th century? What was the most important legal right achieved by American women? Historians point to the gradual, state-by-state, laws finally passed permitting married women to own their own property - and eventually, by the end of the century, to own their own earnings. Rhode Island passed these so-called progressive laws in the 1840s and 1870s.

Why had I never known about “coverture” or the “civil death” of the married woman under the English common law tradition brought over into our founding legal system? How come this American history was something I never learned in school growing up? Here is the established 18th century legal definition of a married woman: “by marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law; that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage.”

Abolishing “the disability of coverture” was not a change that happened in a decade, let alone a lifetime. A different kind of cross-generational solidarity helped build the foundations that got us to now.

While researching Rhode Island laws on coverture, I stumbled through our state lawmaker’s unseemly and zealous attention to RI laws governing marriage in 1844. First there is an Act barring intermarriage between relatives, complete with an administrative list specifying who cannot marry whom – from stepmother to grandmother’s husband. (As a genealogist, I can assure you that many Rhode Islanders - for better or for worse - continued to intermarry within tight kinship networks long past this prescriptive law.)

Another law passed for 1844 does begin to address the property rights of married women. However, the patent law scholar, Zorina Khan, argues in The Democratization of Invention (2005) that these first married women’s property right laws passed in the late 1830s and 1840s are not really about women’s rights. Rather, she sees them as adjustments to bankruptcy law in the aftermath of business failures brought on by the Panic of 1837. That is, these changes to coverture law are a response to bankrupt husbands ruined by the uncertainties of a market economy, and the new need to offset the public cost of supporting now-destitute women and children.

Thus, one Rhode Island law legislated against traditional arranged marriages within family kinship networks, while another law took steps to return the risks wrought by a changing market economy back on to the individual mother in a now more-nuclear family unit.

Marriage was certainly a public act in the eyes of the state in 1844. There was an Act requiring every marriage, birth and death to be registered for the fee of ten cents. And there was a separate and intricate Act to prevent Clandestine Marriages. It takes my breathe away every time to read the final section of this Act: “No person by this act authorized to join persons in marriage shall join in marriage any white person with any negro, indian or mulatto, on the penalty of two hundred dollars; …” More sobering is the news that various Rhode Island laws prohibited interracial marriage from about 1800 - 1960. The last interracial marriage law in America was not overturned until 2000.

In the 21st century, Rhode Island is rightfully proud of enacting the Marriage Equality Bill in May 2013. And while I was writing this blog post today in early October 2014, the United States Supreme Court surprised the legal landscape by not taking on a major case that hoped to legally block same-sex marriage in the five states of Indiana, Oklahoma, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin. Will the door to progressive change stay open, this time? And if not, in what unexpected form might retrenchment take?

The law is itself a tool of power and lucky are those who always stand tall in its sight. To tell this story fully is to note not only the slow pace of legal change but also the struggles and resilience of others set apart by the powerful language of law. This story too has a long history. In Elaine Forman Crane’s outstanding historical survey, Ebb Tide in New England: Women, Seaports and Social Change 1630-1800 (1998), she quickly surveys 2000 years of property law before focusing on English common law and the rules governing men, women, and property in the colonial settlements of New England and then the early republic. Crane makes the case that the growth of an American legal infrastructure in itself shut women out of liberties they once possessed. And yet, she notes the many ways women resisted laws and created generous lives skirting the need for legal contracts, for example.

I would love to believe that we live in an enlightened, post-feminist 21st century and that this history is behind us; that the past has passed. But I do not.

To be sure, dedicated men and women are working together in the trenches of our imperfect legal system to advance women’s issues bit by bit. (And plenty of people of both genders seem to be in the fray only to advance themselves.) But the hurdles are still high for mentoring and then electing a generation of women who will take their rightful place in the room making the marriage, property and contract laws that affect all of us whether we like it or not.

Yes, we have come a long ways – but there is a lot to do right now and for generations still to come. For some, it will be shaping policy and law. And for others, perhaps something as basic as really listening to how one or a million mothers raised the next generation. (Most likely it was without a contract.)

P.S. - I mentioned in my September post the incredible sound byte that in Rhode Island’s 350+ year history only seven women had been elected to state wide office – and all since 1982.

People wanted to know who they are, so I’m responding here. As of October 2014 the seven women are:

RI Secretary of State:

Susan Lawson Farmer, elected 1982-1986Kathleen S. Connell, elected 1986-1993Barbara Martin Leonard, elected 1992-1995

RI Attorney General:

Arlene Violet, elected 1984-1986

RI General Treasurer:

Nancy J. Mayer, elected 1992 -1999Gina Raimondo, elected 2010 - present

RI Lieutenant Governor:

Elizabeth Roberts, elected 2006-2014

Nancy Austin is a student of Rhode Island's history. She has taught at RISD, Yale, and WPI and received her Ph.D. from Brown University in 2009 with a thesis on the founding of RISD and its Museum.

Nancy believes now is a time for public history activism beyond the classroom. She offers her skills as an expert archival researcher and innovative critical thinker to help individuals, institutions, and places discover new strategic opportunities based on their own untold stories. Stay tuned on the RightHer Blog to follow her series on transformative historical moments that have impacted Rhode Island women's economic opportunities. Follow Nancy on Twitter @AustinAlchemy.

Contents of this blog constitute the opinion of the author, and the author alone; they do not represent the views and opinions of Women' s Fund of Rhode Island.